Basic Strength Training the Proper Way: An Overview

Often overlooked is the pivotal role of a basic strength training routine in maintaining functionality for everyday life. Contrary to popular belief, the decline in muscle and bone mass, metabolic rate, and the accumulation of fat aren't inevitable outcomes of aging. This article endeavors to elucidate the various training variables and methodologies, serving as an educational primer on the rudiments of strength training.

STRENGTH TRAININGRESISTANCE TRAINING

7/9/202413 min read

A lot of people do not realize that dieting alone has never proven to be an effective intervention for permanent weight loss and sustained weight management; and the exercise program should not be limited to only aerobic activity (e.g., walking, running, cycling) [7]. In fact, a sensible combination of diet, aerobic activity, and strength training can produce simultaneous fat loss and muscle gain [7]. While muscular strength is suggested to be a critical attribute for many athletic disciplines, it is also an essential component of functionality in daily living. In this article, we will focus on strength training, specifically its benefits, influential factors, and methods.

Strength Training Benefits

Muscle is very active tissue that makes up about half of the body’s lean weight (i.e., muscle, bone, blood, skin, organs, and connective tissue). The number one thing that you should understand is that muscle plays a major role in metabolism and weight management. Muscle tissue is constantly active. Even during sleep, resting skeletal muscles handle more than 25% of the body’s caloric expenditure [2]. Furthermore, strength training raises your resting metabolic rate (RMR) and results in more calories burned daily. Strength trained muscle burns about 50% more calories/day compared to non-strength trained muscle. Additionally, it is critical that you make strength training a regular component of an active lifestyle. Physical capacity decreases dramatically with age in non-strength training adults due to an average 5-lb. (2.3 kg) per decade loss of muscle tissue, known as disuse atrophy [2]. This phenomenon can be avoided with regular strength training. Numerous strength-training studies have shown that several weeks of traditional strength training result in about 3 lbs. (1.4 kg) more muscle and 4 lbs. (1.8 kg) less fat in adults and older adults, and this rate of body-composition improvement appears to continue for several months [2]. There are several benefits associated with strength training [7].

Strength training is effective for:

Increasing muscle mass

Raising resting metabolic rate (RMR)

Reducing body fat

Increasing bone density

Enhancing insulin sensitivity and glycemic control

Reducing resting blood pressure

Improving blood lipid profiles

Enhancing vascular condition

Improving cognitive function

Increasing self-esteem

Reducing depression

Decreasing musculoskeletal discomfort

Reversing specific aging factors

Facilitating physical function

Training Variables

There are several training variables that affect the rate and degree of strength development and should be considered before starting a strength training regimen. These variables are frequency, speed, volume, intensity, rest intervals, and exercise selection/order.

Frequency. Training frequency is inversely related to both training volume and training intensity. In other words, high-volume/high-intensity strength workouts produce more muscle microtrauma, require more time for tissue remodeling, and therefore must be performed less often for optimal results [2]. The microtrauma-repair and muscle-remodeling processes require at least 72 hours following a challenging strength training session [2]. Studies with advanced lifters indicate that optimal muscle remodeling occurs between 72 and 96 hours after a challenging strength training session [7]. The following table provides general training frequency guidelines for beginner, intermediate, and advanced lifters.

General Training Frequency Guidelines

Experience Level Sessions Per Week

Beginner (not currently training or just beginning with minimal skill) 2-3

Intermediate (basic skill) 3-4

Advanced (advanced skill) 4-7

Data from: Baechle, T.R. & Earle, R.W. (2008). Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning (3rd ed.). Champaign, III.: Human Kinetics.

Speed. Resistance exercise should be performed with both controlled lifting (concentric) and controlled lowering (eccentric) movements to maximize muscle activation throughout each repetition. Research indicates that moderate-to-slow repetition speeds provide more muscle tension, more continuous muscle force, less momentum, and less tissue trauma than fast movement (jerking) speeds [7]. A movement speed of 4-8 seconds offers a safe, practical, and productive means for increasing muscle strength and size [7]. Therefore, each exercise should be performed slow and controlled so that the concentric and eccentric phases each take about 2-3 seconds to complete with more emphasis placed on the eccentric phase [7].

Volume. Training volume is usually lower in strength training regimens (i.e., 2-6 sets and ≤6 repetitions per set), because the focus is on improving the muscle’s ability to maximally recruit fibers to generate higher amounts of force to lift heavy weight loads [2]. Muscular strength can be significantly increased through either single-set or multiple-set training. Due to the lack of consensus regarding the optimum number of training sets, novice lifters should perform one good set of each exercise and more experienced lifters, who desire greater volume, can perform two or more sets [7].

Intensity. Muscular strength is measured by the heaviest weight load that can be lifted one time through a full range of motion (ROM), with correct technique, and with controlled speed. This is referred to as the one-repetition maximum (1-RM). Strength training programs are typically designed around this number. The 1-RM is the intensity (i.e., the weight lifted). For optimal strength development, most authorities recommend weight loads between 80 and 90% of the 1-RM [2]. Exercises with near-maximal weight loads that allow 1-3 repetitions with more than 90% of maximal resistance are highly effective for developing muscular strength [2]. Because these are relatively heavy weight loads, a periodized approach that progressively increases the training intensity over several weeks is recommended. Muscle strength can also be developed effectively by working the target muscle to fatigue within the body’s anaerobic energy system. This is about 50-70 seconds of continuous muscle work with 75% of the 1-RM [2]. This number can be estimated without doing an all-out lift; the weight that can be lifted 10 times to fatigue is approximately 75% of maximum resistance.

Rest Intervals. The heavier the load, the longer the rest interval needed for recovery, because a high effort set reduces the muscle’s internal energy stores of creatine phosphate [2]. These energy stores replenish quickly, with 50% renewal within the first 30 seconds, 75% renewal within the first minute, and 95% renewal within the first 2 minutes [2]. Longer rest intervals allow the use of relatively heavy weight loads throughout the training session. Therefore, lifters interested in maximizing muscular strength usually take 2-5 minutes of rest between sets of the same exercise [2].

Exercise Selection/Order. Generally, linear exercises that involve multiple muscle groups are the preferred method for increasing total-body strength. These exercises include squats, deadlifts, or leg presses for the squat pattern; step-ups and lunges for the lunge pattern; bench presses, incline presses, shoulder presses, and bar dips for the push pattern; and seated rows, lat pull-downs, and pull-ups for the pulling pattern [2]. Rotary exercises that isolate specific muscle groups (e.g., leg extensions, leg curls, hip adductions, hip abductions, lateral raises, chest crossovers, pull-overs, arm extensions, arm curls, trunk extensions, and trunk curls) should not be excluded from muscular-strength workouts, but these typically play a lesser role than the movement-based exercises that challenge multiple muscles at the same time [2].

There are a variety of methods to enhance muscular strength, size, endurance, and performance [2]:

Performing primary, multi-joint linear exercises followed by secondary, single-joint rotary exercises for a specific muscle group (e.g., squats followed by leg extensions).

Alternating upper- and lower-extremity exercises within or between training sessions.

Grouping pushing and pulling movements or targeting joint agonists and antagonists during a session (e.g., chest and back or triceps and biceps).

Performing supersets or compound sets where exercises are done in sequence with little or no rest between them.

Simply training will not guarantee results, therefore organizing your training sessions and selecting the most effective exercises and methods will enhance the outcomes.

Strength Training Methods

Double-Progressive Training Protocol. There are two main approaches to strength-training progression. The first and simplest method is to increase the number of repetitions. The second method is to increase the training resistance. This is known as the double-progressive training approach. Increasing the number of repetitions and then increasing the weight load by 5% ensures gradual strength gains, with a relatively low risk of injury [2]. Assuming a repetition range of 8-12 repetitions per set, a double-progressive training protocol would be applied in the following manner. An individual can presently perform 8 squats with 205 lbs. (93 kg). The individual continues to train with this weight load until he or she can complete 12 repetitions with the same weight. At that point, the weight is increased by 5% to 215 lbs. (98 kg). The heavier weight load reduces the number of squats to 10 repetitions. The individual continues to train with 215 lbs. (98 kg) until 12 repetitions are reached, after which point the weight is increased again by 5% to 225 lbs. (102 kg) and so on. There is no time limit with this approach. Whether it takes one week or one month, the resistance is increased only when the end-range repetition number can be completed with proper form [2].

Periodization Theory. Strength training programs manipulate the training variables (e.g., volume, intensity, and exercise selection) to elicit specific training and performance goals [4, 6]. This methodical approach is known as the Theory of Periodization, which is very effective for attaining strength development and peak performance. The advantage of periodized over non-periodized exercise programs is the often-changing demands on the neuromuscular system that require progressively higher levels of stress adaptation [2]. An example of this training process would be a 3-month program of exercise periodization that progresses from higher repetitions with lower intensity to lower repetitions with higher intensity, shown in the table below.

Month Exercise Intensity Exercise Repetitions

1st 65% of 1-RM 12-16 reps/set

2nd 75% of 1-RM 8-12 reps/set

3rd 85% of 1-RM 4-8 reps/set

Data from: Westcott, W. L. (2020). Strength Training Essentials. Healthy Learning.

In the first month, the lower intensity provides less stress to the muscles, tendons, ligaments, and bones, thereby reducing the risk of tissue injury during the initial conditioning phase. The second month begins to provide a strength training stimulus, preparing the body for the final training phase. In the third month, the higher intensity provides greater strength stimulus and should be well tolerated by the musculoskeletal system after two months of progressive conditioning.

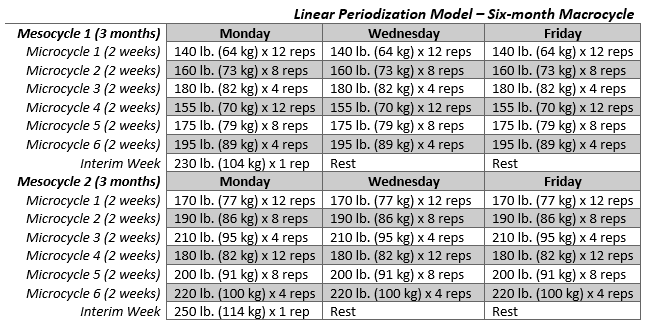

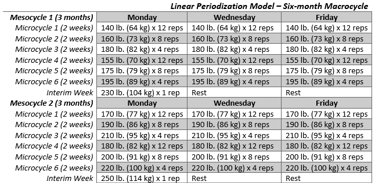

Periodization programs can be 6-12 months in training duration [2]. The overall time frame is termed the macrocycle, which is further broken down into mesocycles (i.e., months) and microcycles (i.e., weeks) [2, 6]. There are two different periodization models: linear and undulating. The linear periodization model is characterized by an initial period of high training volume and low intensity and gradually progresses toward lower training volume and higher intensity over the course of several months [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. An example of a linear periodization model for a bench press training program is shown below. This individual has a goal of bench pressing 250 lbs. (114 kg) with a current 1-RM of 200 lbs. (91 kg). The goal of the first mesocycle is to bench press 230 lbs. (104 kg), and the goal of the second mesocycle is to bench press the established goal of 250 lbs. (114 kg). There are 12 microcycles of two weeks each. The training weight load progressions are consistent with research data, but the recommended number of repetitions may not apply to everyone. This individual should perform as many repetitions as possible with each exercise set, even if it’s slightly lower or higher than the target number. It is recommended that the individual perform two progressive bench press warm-up sets followed by two sets with the training weight load [2].

Note: Although the strength-training program includes exercises for all the major muscle groups, only the bench press protocols are shown.

Data from: Bryant, C. X., Jo, S., & Green, D. J. (Eds.). (2014). ACE Personal Trainer Manual (5th ed.). American Council on Exercise.

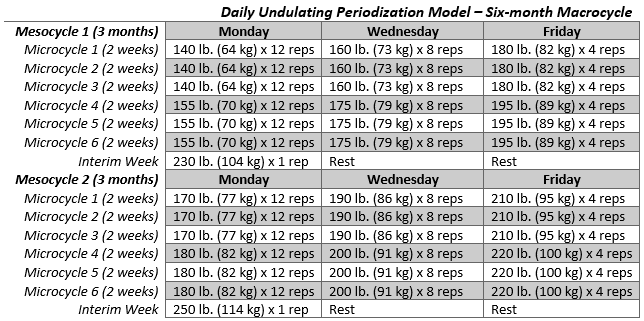

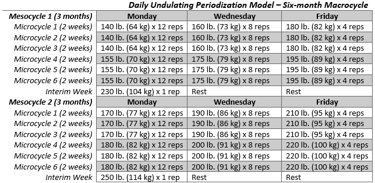

The undulating (or “non-linear”) periodization model is characterized by frequent variations in training volume and intensity that can vary on a cyclical, weekly, or daily basis [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. An example of a daily undulating periodization model for the sample bench press training program is shown below.

Data from: Bryant, C. X., Jo, S., & Green, D. J. (Eds.). (2014). ACE Personal Trainer Manual (5th ed.). American Council on Exercise.

For a training program to remain effective, it must continually overload the neuromuscular system [4]. Research has demonstrated that men and women of all ages and varying training experiences attain greater strength gains when following a periodized training program [1]. Furthermore, the undulating periodization model may produce superior and faster strength gains due to its frequent variations in loading [1, 3, 4, 5]. However, both the linear and undulating periodization models are highly effective for novice lifters for developing muscular strength [3].

Various other more effective methods exist for developing strength, and all stem from Periodization Theory. Some of these methods include the Starting Strength Model, the Texas Method, the Split Routine Model, and the HLM model. An in-depth explanation of all these methods and how to implement them can be found in the AnlianFitness Resistance Training Manual.

Additional Considerations

Safety. Adherence to correct exercise form is critical, otherwise risk of muscle, tendon, and connective tissue injury may be increased, and improvement potential may be decreased. Another important aspect of strength training is making sure that you train muscle antagonists [7]. Training one muscle without training its opposing muscle will lead to a muscle imbalance, which will, in time, compromise joint integrity because one muscle will become disproportionately stronger than its antagonist. More safety considerations include proper warmups and breathing techniques. Warming up increases internal body temperature, which, in turn, enhances muscle elasticity and extensibility; therefore, individuals who warm up before engaging in strength training should be less prone to muscle, tendon, and connective tissue injury [7]. Examples of warmup activities include stationary cycling, jogging in place, calisthenics, and performing lighter lifting sets prior to doing the heavier sets. Holding your breath while strength training may create an undesirable “Valsalva maneuver.” This can be avoided with a proper breathing pattern while training, i.e., inhaling during the eccentric phase and exhaling during the concentric phase of each repetition [7]. Other safety considerations include using a well-trained spotter, wearing proper clothing, and effectively managing muscle soreness [7].

Adaptation Principle. Given enough time, the training stimulus can either have a positive or negative impact on the human body. In other words, there exists a threshold at which the body’s positive adaptation or overcompensation will seize, and any added stress on the body will have a negative effect, known as overtraining [1]. If the stress is too high during a training session (i.e., high levels of tissue microtrauma occurrence), the muscles could react negatively. It is common to experience several days of muscle weakness, fatigue, and discomfort, known as Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS); however, this may not lead to enhanced muscle size and strength [1]. Conversely, when muscles are systematically stressed in a progressive way where the training stress is adequately high, the resulting low levels of tissue microtrauma elicits muscle-remodeling processes that lead to larger and stronger muscles [1]. Positive adaptation is dependent on a few factors [1].

Perform each exercise through a full range of motion (ROM).

Muscular adaptation happens faster than tendons and ligaments, therefore, the latter requires more training time to respond adequately and reduce injury risk.

To develop the strength of arms and legs, it is necessary to develop the trunk (i.e., core).

The primary muscles work better when the muscle stabilizers are strong.

Recovery time is proportional to the stress intensity.

Periodization training is based on the adaptation principle.

ROM. Performing each exercise through a full range of motion (ROM) will develop full-range strength, enhance joint flexibility, and make you less prone to injuries [7]. Strength training will not make you “musclebound” [7]. Furthermore, full-range muscle strength is especially important for people with low back pain, therefore, full ROM resistance exercise should be performed whenever possible [7].

Reversibility. Muscle reversibility is the phenomenon of gradually losing muscle size and strength due to detraining (ceasing resistance exercise). If you stop performing resistance exercise, you will lose strength at about one-half the rate that it was gained [2]. In other words, if you increased your squat strength by 50% over a 10-week training period, you would lose half of that strength gain after 10 weeks of no resistance training and all your strength gain after 20 weeks of no resistance training. Detraining also results in reversal of many health and fitness benefits associated with regular resistance training [7]. Therefore, if you wish to keep your gains, it is in your best interest to make resistance training a regular component of an active lifestyle.

Conclusion

Many assume that muscle and bone loss, metabolic slowdown, and fat gain are inevitable consequences of the aging process. This is simply not true. Research demonstrates that by performing strength training consistently and properly, men and women of all ages can add muscle, rebuild bone, recharge metabolism, and reduce fat [7]. However, without incorporating basic strength training into a daily or weekly regimen, you will lose up to 10% of your muscle mass and up to 30% of your bone mass per decade [7]. Nobody wants this, and it's never too late to start. We hope that this overview has provided you with a solid foundation on the basics of strength training.

Sources

[1] Bertucci, D. R., & Ferraresi, C. (2016). Strength Training: Methods, Health Benefits and Doping. Nova Science Publishers. https://eds-s-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/eds/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzExMzQ0NTZfX0FO0?sid=b5e6955f-8aa1-4fff-906c-5bba28f3d5d2@redis&vid=1&format=EB&rid=1

[2] Bryant, C. X., Jo, S., & Green, D. J. (Eds.). (2014). ACE Personal Trainer Manual (5th ed.). American Council on Exercise.

[3] Déborah De Araújo Farias, Michel Moraes Gonçalves, Sérgio Eduardo Nassar, & Euzébio De Oliveira. (2021). Effects of Different Periodization Models in Strength Training on Physical and Motor Skills during 24 Weeks of Training. Journal of Physical Education, 90(2), 118-133. https://doi.org/10.37310/ref.v90i2.2793

[4] Evans, J. W. (2019). Periodized Resistance Training for Enhancing Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy and Strength: A Mini-Review. Frontiers in Physiology, 10, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.00013

[5] Jiménez, A. (2009). Undulating periodization models for strength training & conditioning. Motricidade, 5(3), 1-5. http://ezproxy.umgc.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edb&AN=51639958&site=eds-live&scope=site

[6] Kai, J. T. (2010). Strength Training: Types and Principles, Benefits and Concerns. Nova Science Publishers. https://eds-s-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.umgc.edu/eds/ebookviewer/ebook/bmxlYmtfXzM1Mjc1MV9fQU41?sid=b5e6955f-8aa1-4fff-906c-5bba28f3d5d2@redis&vid=3&format=EB&rid=2

[7] Westcott, W. L. (2020). Strength Training Essentials. Healthy Learning.

Copyright © 2024-2025 AnlianFitness. All rights reserved.

Follow us on social media.